Author: Matt Wittern, APR, PMP, Senior Consultant (Email)

Anxiety. Excitement. Dread. Opportunity for impact.

These are just a sampling of responses I’ve collected when asking workshop participants to share the word or feeling that comes to mind when they imagine themselves starting a brand new project.

It’s easy to understand why – a report by Wellingtone, a UK-based Project Management company, revealed that only half of companies say they have a track record of project success[1].

It can hardly be better in the public sector. We can all think of headlines when a high-profile project goes over budget – Boston has the Big Dig, Denver has its current challenge with Denver International Airport, the list goes on.

On the positive side, a new project can be exciting – an opportunity to break away from the everyday. To lead a team brought together for a specific purpose and look forward to the pride you will take in a job well done.

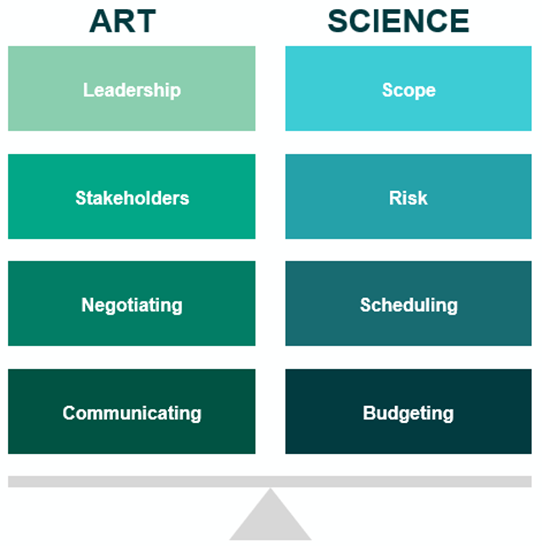

As I recently told a group of public information officers during a webinar presentation, it’s my experience that communicators have a leg up on at least half of what it takes to be a good project manager. The reason for this is there is a balance of art and science when looking at the ideal project manager’s skillsets:

On the art side, we are already leaders when it comes to helping our organizations head in the right direction. We are always thinking about stakeholders – what they are thinking and how we can work better with them. We’re also experts at negotiating, building relationships with people that results in a give and take that benefits both parties. And finally, we’re all skilled at communicating, which is embedded in every task listed above.

Where some communicators can use help in project management is on the science side. We can get in trouble when it comes to scope because at some level we are all people pleasers, and it can be difficult to say no to “just one more thing.” Also, I find we are prone to not properly accounting for risk, in that many of us have the tendency to worry about the worst happening when the actual chances of that are often miniscule. The last two – scheduling and budgeting are too often managed in our heads, which can make it difficult to share details with others and introduces opportunities for errors.

In simple terms, scope is the extent of a given activity – in this case, your project. Identifying the scope helps everyone involved understand what the project is meant to accomplish. If you drew a circle, it would encompass everything you are charged with doing. Everything else is outside the scope, outside the circle.

Nobody knows it better than communications professionals that no matter the organization, all resources are finite. On one end of the spectrum, developing a clear scope helps determine the minimum level of resources that will be necessary to accomplish the objectives. On the other end, a clearly-defined scope helps keep the project focused and better able to brush off the all-too-frequent future requests to broaden the project, or to add “gold plating” that isn’t necessary to achieve the intended goals.

As consultants, everything we do in support of or on behalf of clients are projects. When starting one, we always host a kickoff meeting that includes all the key decision-makers within the organization. A guided discussion is helpful for teasing out a host of elements that inform our tailored communications strategy. Among the questions we ask to help set the scope include:

Often, by sharing our screen or projecting it on the wall, we’re able to work together to emerge from the kickoff meeting with agreement on a scope statement to guide our work. More specific than a mission statement, a scope statement can be seen as the circle referenced above and becomes the focus of the project.

For communicators within organizations, securing group agreement on the project scope delivers benefits including:

It’s so common it’s become cliché – a consultant asking a potential client “what keeps you up at night?” At its core, this question is rooted in risk, which for our purposes can be defined as the chance of running into a hazard or incurring a loss.

The good news is that, for the most part, risk can be managed. The science of risk management has kept insurance companies functioning for millennia, but communicators don’t need complicated actuarial tables. For communicators, we can use a risk register, which is a straightforward document that enables us to list potential risks, rate the likelihood of it taking place, the impact on the project if it were to take place, and steps we can take to avoid or mitigate the risk.

Using a risk register includes the following components:

Developing and maintaining a risk register will help you as a project manager sleep better at night, content in the knowledge that you have a thorough accounting of risks that can negatively impact your project. Sharing this document with your supervisors will give them confidence that you have this key element of the project well in-hand.

As communicators, we understand the value of graphics to share information in a way that is more appealing to the reader than regular text. An indispensable tool in project management is a schedule, and there are few better ways to display a schedule than use of a Gantt chart, a tool invented by Henry Gantt, a mechanical engineer in the early 20th century.

Gantt charts display your project schedule horizontally along a timeline that show start and end dates of specific activities, whether an activity is dependent on successfully completing a previous task entry, who is responsible for specific tasks, critical milestones and deadlines, etc.

As a communication tool, a Gantt chart isn’t just great for giving transparency to the process. It helps your teammates predict when they will be asked to perform a specific task, which helps them manage workload. It increases accountability, with everyone understanding what (and when) something will be expected of them. They are also useful as a tool to lead successful project meetings and can be living documents that help you track the team’s progress.

Gantt charts typically:

Until recently, Gantt charts were created using complex (and expensive) project management software, or built from scratch using tools like Microsoft Project or Excel. Fortunately for my fellow communicators who might be intimidated by those programs, the internet has enabled a wide variety of startups that deliver web-based Gantt charts that are simple enough to have a short learning curve, but effective and attractive enough to make your project look very professional. As of this writing, a handful of providers included:

A mentor of mine occasionally quips that she should never be permitted to “do math in public,” and I’m confident that sentiment is shared by communication colleagues; it certainly is for me. For many of us, an appeal of our chosen profession is the low expectation of our abilities in mathematics, but that runs into trouble when we mix communications and project management.

Budgeting is a core skillset for effective project managers, but it doesn’t have to be as intimidating as it seems initially. It’s also a key tool to make the case for adequate funding – also known as the life blood of most projects – something we communicators have too often functioned without. So, what are the key elements of a project budget? Not all of these are likely to apply, but consider:

Like other aspects of project management, budgeting is a task that should not be attempted alone – draw upon resources you have available to you, including:

When viewed through this lens, I hope it is clear just how well positioned most strategic communications professionals are to improve their project management skills and balance the scale of arts and science. Technology is always improving to help us with these skills, and tools developed on prior projects can easily be repurposed as templates to make your next one even more successful than the last.

[1] https://www.wellingtone.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/The-State-of-Project-Management-Survey-2018-FINAL.pdf