Author: Sam Villegas, Principal Consultant (Email)

Public meetings—they’ve become the bane of our existence. Simply search on “bad public meeting” in You Tube and you will be served up hundreds of incredible videos of a seemingly civil assembly devolving into fisticuffs in a matter of minutes. The hit show “Parks and Recreation” has a gem of a segment on public meetings that’s worth the three minutes if you want a good laugh. It was meant as satire, but given the experiences I have had, it’s little closer to reality than I think any of us would prefer. And this was even before Covid. Ever since March 2020, it seems public meetings have gotten worse. And I get it. Tensions are high. Patience is low. And even the most seemingly benign topics have become politicized or controversial. In many cases, we schedule a town hall-type public meeting as the default. It’s what we’ve always done, and very little critical thinking goes into it.

What’s wrong with the Town Hall you ask? Only everything. From the way it’s set up to the way it’s often managed, there is little value for both the presenter and the audience. Some of the key drawbacks of this traditional public meeting are:

Let’s first address the problem with the set up. The agency (and your team) is often at the front of the room, sometimes on a stage or a dais. Your stakeholders then sit on rows of chairs facing you, oftentimes, physically lower than you. This sets up an unequal power dynamic that favors your staff or elected official. While you may benefit from that dynamic, it does not build community, trust, or create an environment where guests feel empowered or relaxed. In fact, this set-up is often the reason emotions tend to escalate fast. People feel physically disadvantaged merely by where they sit.

In addition, your audience has decreasing visibility the further back they sit. They may also have decreased ability to hear you, the further they sit back. The seating is often close knit, which was politely tolerated before the pandemic, but now feels straight up uncomfortable for most people. Folks in a wheelchair or those with strollers are forced to the sides or the back, and those without childcare have brought their children with them. These may feel like small inconveniences to you, but for an audience member the slight feels large and cumulative. You have cramped them together, uncomfortably, in a spot where they may be challenged to see you, hear you, or even cross their legs. All this and we haven’t even addressed the lighting and temperature in the room.

Let’s also consider the timing. These meetings are usually on a weeknight as a nod of accommodating those who work during the day, but this carries with it the assumption that most interested stakeholders work the kind of job, or have the kind of household, that enables them to attend a meeting on a weeknight evening. Can someone who works the night shift attend? Can a mother of young children with early bedtimes attend? How about a senior who can’t drive so well at night? Where is the meeting located? Is it accessible by public transportation? Does the parking lot have ample spaces?

Finally, the format. Typically the agency gives a 20- or 30-minute PowerPoint presentation with a bunch of dry slides with have a lot of text on them, then opens it up for questions or feedback. Then staff members circulate a microphone to attendees in the audience, who then have an opportunity to say their piece while staff enforces a 3-minute time limit on how long a participant can speak.

Sometimes this goes relatively smoothly, and several people make comments and ask questions and then everyone goes home satisfied. With growing frequency however, attendees at Town Hall style public meetings become emotional. They’re not happy with what they’re hearing. They don’t trust the agency’s information or intentions and they’re not sure anything they say will even make a difference. So they raise their voices. Or they monopolize the night. Or they accuse. Some even get physically threatening.

These are not bad people, so why are they acting this way? They are likely angry or emotional out of fear. And they are fearful due to an absence of trust in you. And there’s an absence of trust likely because there hasn’t been good, clear, consistent, transparent communication from your agency. So, if your goals include obtaining real understanding and trust from your stakeholders; conversations not lectures; insights not insults; or thoughtful consideration and input as opposed to drama and threats, then it may be time for you to torch the Town Hall.

The very next time you think you need a public meeting because you want feedback on something or because you are planning something controversial, take out a fresh sheet of paper. Write at the very top, “What is the Purpose of this Meeting?” Get a group from your leadership together and ask yourselves some key questions, such as:

By answering these questions, you will start to see why the Town Hall is problematic and may also start to brainstorm better ways to achieve your result.

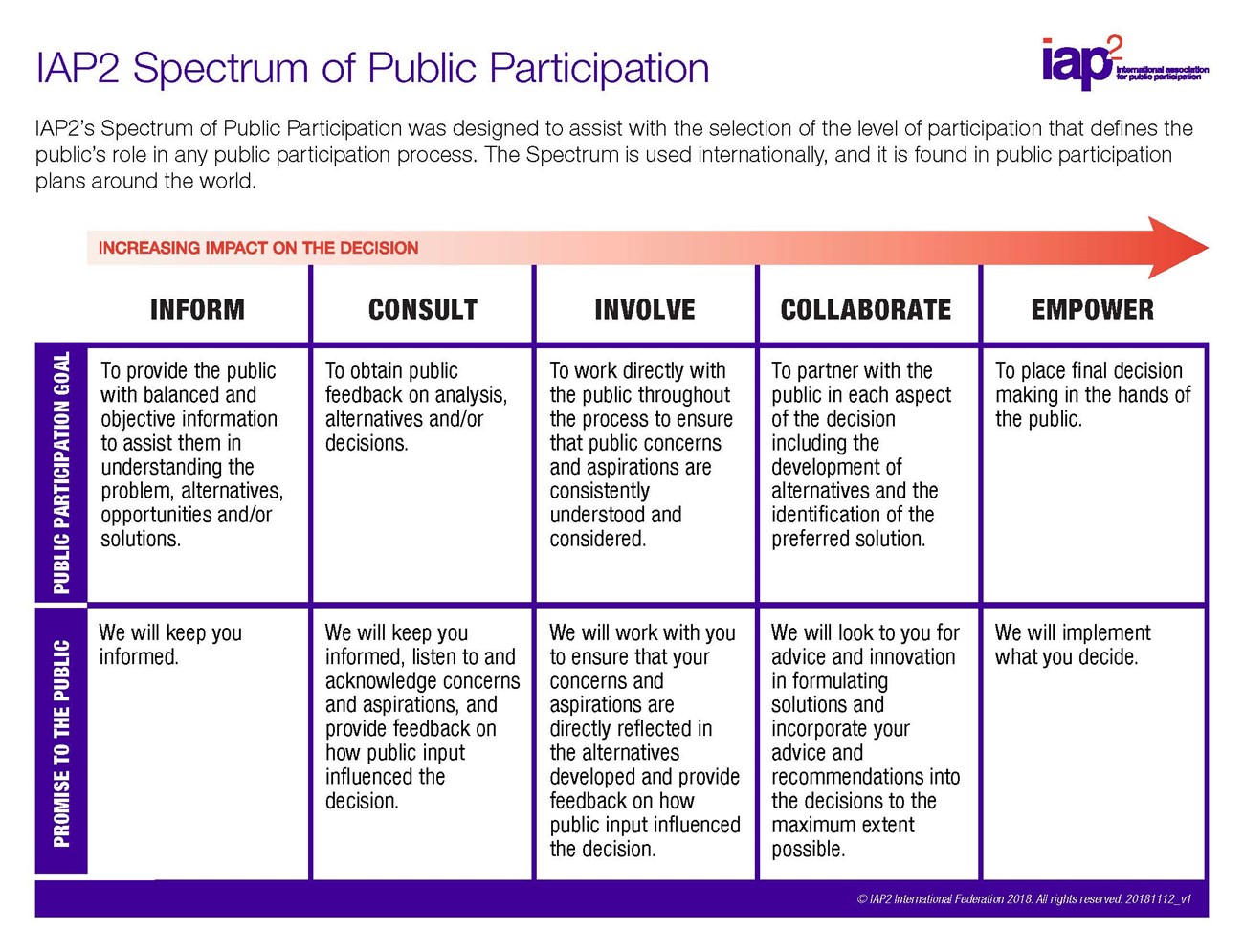

Image courtesy of IAP2 International Federation

So, if not the tortured Town Hall, what should your agency do? Technique selection is important and should not be random. The image here is the International Association of Public Participation’s (IAP2) Spectrum of Public Participation opportunities. As we move left to right, we are moving from a high-trust to low-trust environment AND a low emotion/controversy to high emotion/high controversy. A public meeting is a technique best reserved for a high trust, low conflict, low emotion, low controversial subject. So, when you are certain that’s the environment you have, then a public meeting may be okay. But if you think you have something higher emotion/higher controversy and/or, there is lower trust in your agency, then you’re going to want to choose a different technique to engage with your stakeholders. Here are some useful techniques you can use that will yield much more satisfying and meaningful results for you and your stakeholders:

If you are merely informing your stakeholders of something, like announcing the launch of a program or new policy or initiative and no real input from the audience is being sought, there are myriad ways to get that information out, and you can customize the way you deliver that announcement to assure it meets the specific audience you hope to reach, such as using an HOA newsletter to reach a certain area of homeowners about a project that may impact them. Or, by providing materials and talking points to a social service organization about an affordability program you are launching, targeted to low-income households. Or, submitting an article to a city newsletter or providing a fact sheet to a senior center to reach your community’s seniors with critical information on a new program that serves them.

If you want to inform and also collect some feedback, there are a number of simple, low-cost techniques you can use.

Influencer Interviews – Influencer interviews are a great way to get insights before you start communicating about a project. Usually completed at the very beginning of your project, a series of a dozen or so 30-minute interviews with some of the most knowledgeable and influential members of your community can give you a line of sight into what folks may be thinking or perceiving about the topic at hand, or about your agency, or both. You can get an early read into “third rail” topics (too hot to touch) or see if words or terms you intend to use mean what you intend them to mean.

Digital Survey – A digital survey, using an online tool like Survey Monkey or Zoho for example, gives you a chance to obtain quantitative information from your stakeholders. This works best when you want to obtain a baseline understanding of your stakeholder’s knowledge or behaviors around a particular topic prior to beginning your outreach, so you can later measure how effective the communication was. The survey typically uses close-ended questions. A sample size of 400 will generally yield you results that are statistically significant, meaning, the results you see after 400 completed surveys are not likely to change much with additional surveys completed.

Open House – An Open House is an excellent alternative to the Town Hall because it removes the potential for big conflicts, shouting matches, and mayhem. With an Open House, people don’t have the opportunity to grandstand in front of a crowded room. Instead, guests can view a pre-recorded presentation on loop in one spot, then visit different tables with different large maps and images and speak one-on-one with subject matter experts, who can give their focused attention to each stakeholder, and listen for issues, pain points and ideas.

The Open House enables participation from a more diverse audience. Instead of only accommodating those who can make a specific time, you can host an Open House several days at different times over a week. If you offer childcare and set up the room appropriately, then you expand your inclusivity of diverse stakeholders.

Online Open House – Just like you did in person, you can set up a virtual meeting with a slide show presentation, then send attendees into small group breakout rooms with project team members who can ask a series of questions and seek input from the attendees. There are tools like Turning Point Solutions and Poll Everywhere that enable you to poll your audiences. Zoom has built-in polling capabilities. Other online tools like Google’s Jam Board or Mural enable brainstorming and prioritization activities by attendees, all anonymously.

The Involve level takes the act of obtaining input a step further. The biggest difference between the Consult and Involve step is Involve tends to mean an ongoing consultation is happening. It’s not a “one-and-done” effort, but something more enduring over the life of the project or study. In this case, your engagement may include meeting with several key groups of stakeholders multiple times.

Panels – For a longer-term or higher stake/higher emotional project, it can be very beneficial to obtain ongoing feedback from a panel before decisions are made. Panels are exceptionally valuable when you are seeking to change your water or recycling rates; build a massive structure in a community; or create a new fee. Using a panel throughout the project development phase and before major decisions are made has many benefits. In addition to helping you arrive at a solution that has the input of the stakeholders affected by the decision; you win their trust and respect by including them in the process.

As we move across the spectrum to the right, the project’s impact to stakeholders is higher and/or emotion or controversy is higher. Though in some cases, collaboration is warranted not because of impacts or controversary, but merely because the public has low trust in your agency. This level of engagement for the project is a great way to rebuild that trust. Generally, when you are collaborating, you have moved beyond gathering input from stakeholders. At this point you are developing solutions and concepts together. This might be the case for a major downtown redevelopment project or a community’s comprehensive planning. One of the main techniques well-suited to this level of engagement is the workshop or design charrette. In this case, representative stakeholders are invited in to hear about challenges or opportunities and then they brainstorm, along with the staff, solutions and ideas. Like the Involve stage, this engagement typically occurs over a longer project period.

On the far right of the spectrum is Empower. Up to this point stakeholders have been invited, with growing depth, to provide input into a decision but they have not had decision-making authority. At the Empower stage, stakeholders are actually making decisions. This is rarely done, and often only in extreme cases where the stakes are very high, emotions are high, and trust in the governing body to do the right thing is very low. One example of this may be the siting of a landfill.

For all the reasons described, when clients want help with a traditional public meeting, we often steer them away from the idea. What they really want is shared understanding of a concept; buy-in for a project; and a community that’s cohesive, empowered, inclusive and thriving in every way possible. So torch the town hall and try something a little more civilized for all parties. Getting there is simple but not easy. It takes fresh thinking, an open mind, and a lot of courage. It takes vulnerability and humility and a willingness to change. With some forethought and planning though, the results include more satisfied stakeholders with renewed trust in your agency and a more informed decision that most can support.