A couple weeks later, a customer opens their mailbox to find an oftentimes visually cluttered, incredibly technical, and unappealing document from their water provider. If U.S. Postal Service statistics are correct, it’s competing with nearly 500 other marketing pieces and catalogs that customer will get that year. If the customer opens it and reads it – and that’s a big if – they’ll notice from the first sentence that the language is stilted, uses confusing industry jargon, and reads like a legal document. In the best of cases, they might scan the dense tables of figures, maybe see that their water is safe and then toss it in the recycling bin. In the worst of cases, the customer sees data that scares them. They misinterpret it and instead of contacting your customer service to ask questions and get clarity, they Google, find misinformation, and then go to Facebook or NextDoor to share with their neighbors and the conversation online quickly spirals. In some cases, the local paper writes a story that calls the data and methodology into question, undermining the work you do and chipping away at any trust you may have built with your customers. Next time you go before your board or city council to ask for a rate increase to support investments in your system, your customers are there to quash it, with accusations of unsafe water and mismanaged system.

It doesn’t have to be this way. In fact, the CCR could be the best opportunity a water agency has to develop a strong, trusting relationship with its customers. Many utilities are elevating their CCRs to a higher role – the star of a broad and enduring program about the agency’s ongoing investment and oversight in the public health of its community. Many years ago, Charlotte Water’s Public Affairs Division recognized that their CCR provided an incredibly rare and impactful opportunity to communicate with customers, enhance their brand, build relationships, and make human connections. Their annual Water Quality Report (WQR) was born. While some utilities use the term ‘water quality report” synonymously with CCR, Charlotte Water does not. These refer to two very different documents at Charlotte Water. The CCR is a document that lives on Charlotte Water’s website and it checks the box for EPA’s regulatory requirement. The WQR is something else entirely.

Charlotte Water’s WQR is the alter ego, the sexy cousin, and the better version of the agency’s CCR. It’s the Felix to the CCR’s Oscar. Or, for a more modern reference, it’s the Jacob to the CCR’s Cal (the film Crazy, Stupid, Love). If Charlotte Water’s CCR is a Toyota Corolla, their WQR is a Lexus F. You get the picture. It’s a piece that stands out among its competitors in the mailbox. It focuses on two key factors that influence whether the report gets read or quickly recycled: design and accessibility. It’s these same two factors that Raftelis, Charlotte Water’s 2021 WQR design partner, focused on to create the winning entry to the Environmental Policy Innovation Center’s Water Data Prize Competition last year. Both Charlotte Water and the Raftelis team saw the CCR not for what it is, but for the opportunity it delivers – a rare and critical moment to connect customers to the one thing they can’t go without.

Creating a CCR that does more than meet the requirement – one that actually achieves its namesake – confidence – is not complicated but it does take work. The first step is to understand your customers, their point of reference, their perspective. You have to remember they don’t know water science. They’re not familiar with the language of water quality, and above all, they are not as trusting of government agencies as they used to be. So, understanding what customers think, how they think and how they view the information is an important part of designing a WQR that gets read by them.

Charlotte Water surveyed their customers to understand better, what their customers thought about their tap water, whether they recalled ever seeing the report before, and if so, what elements, if any, did they recall. They asked about how the report made them feel about their tap water and they asked what kinds of information customers would like to know.

Charlotte Water learned from this survey that more customers were drinking tap water than bottled water; though concerns about tap water quality did exist. They learned that the intent of the WQR is being met – it is an incredible tool for building and maintaining trust. More than 67% reported that their trust increased after reading the WQR, while nearly 16% stated their trust in Charlotte Water was maintained at a high level. More than 78% reported they think their water is safer than they thought. More than 20% reported the 2020 WQR explained its purpose “exceptionally well,” while a similar number did not think there was much room for improvement. A little more than a third – 37% – thought it did OK but also thought there is room to improve.

In terms of readability, the 2020 WQR received good marks but there was room for improvement.

In general terms, respondents thought the 2020 WQR did a fair job at defining complicated terms. Those who thought terms were defined satisfactorily or better outnumbered those who thought the definitions were unsatisfactory by at least a two-to-one margin. Among those who did not think they would be likely to read it, more than half stated that the topics did not seem to impact them. Others stated it looked too technical (36%) and others (24%) thought it was too long.

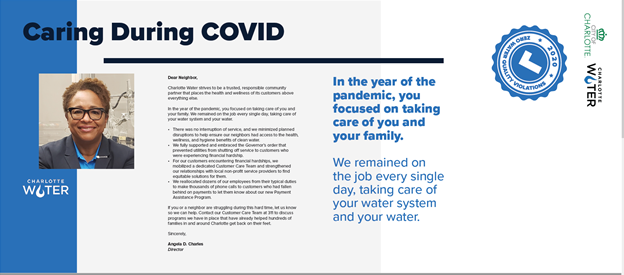

With this feedback in hand, Charlotte Water set out in 2021 to create a WQR in full color, with a higher photo to text ratio and include information about how COVID impacted operations – that staff showed up every day so that despite the massive disruption the Pandemic had on their lives, there was never any disruption to water service. In addition, the Raftelis team ran text through the Flesch-Kincaid review and CDC Clear Communication Index with goal of ensuring reading level no higher than ninth grade and also to ensure the document was ADA compliant.

Note that this isn’t a CCR – it’s a consumer-friendly marketing piece for the CCR – it gives consumers the bottom line info with prompts them to access the full report to learn more. Granted, this does not meet the SDWA requirements for a CCR – not currently at least – but it’s a way to use your money and resources in a thoughtful manner to reach the one goal the CCR is designed to do but fails at miserably – instill confidence in tap water.

Creating a CCR that does more than meet the requirement – one that actually achieves its namesake – confidence – is not complicated but it does take work.

Step 1 The first step is to understand your customers, their point of reference, their perspective. You have to remember they don’t know water science. They’re not familiar with the language of water quality, and above all, they are not as trusting of government agencies as they used to be. Understanding what customers think, how they think, and how they view the information is an important part of designing a WQR that gets read by them. You can learn what they know with informal or formal polling at your website, through social media, by interviewing key figures, or conducting intercept interviews of customers at events.

Step 2 Write for your customer. Use words and phrases that are familiar to them. Use pictures whenever possible to express your point. Use active voice, not passive. Make it easy and interesting for them. Check your readability using Microsoft Word’s editor tool, which can show you what reading level your document is. Aim for eighth to ninth grade.

Step 3 Promote the report’s existence. The “if you build it, they will come” philosophy only works in the movies. Raftelis supported Charlotte Water’s efforts with a full-fledged promotional plan that included goals and measurable success metrics.

The implementation included ways to reach customers of course, like, social media posts, bill inserts, and news releases. More importantly, it included tactics for reaching all the staff to make sure they were aware and empowered to promote it, too, through call center talking points, hold messages, and electronic billboards in offices.

It’s no secret that the CCR in its current form is woefully unsuited to reach consumers with relevant, accessible information that instills confidence in their water quality. EPA is looking at a revision as required under AWIA 2018. The working group’s recommendations center around two key issues: (1) making the CCR more understandable and accessible to all general audiences (so language, education, ADA and (2) providing a better format/template that most utilities can use easily. The recommendations have been submitted and are in EPA’s hands, though they are behind schedule in issuing the new guidelines. In the meantime, some states and nonprofits are seeking ways to keep advancing ideas. Minnesota’s Department of Health, for example, has a portal where they share better templates created by users – templates they have approved for use in their state.

The nonprofit Environmental Policy and Innovation Center (EPIC) is also seeking solutions in a parallel path. They solicited ideas for improving the CCR in 2021 with their annual water data prize. Raftelis’ submittal took first place for its design, data features, and accessibility. This year, with a grant from AWWA, EPIC solicited competitive proposals to develop a template that could better meet the needs of all utilities. Raftelis won that contract, and this is in production now. Come this spring – we will pilot test a new template in several communities that has the blessing of some regulators, and we will hopefully learn from that this year and have an even better template for more wide adoption in 2023 or 2024.

As a large water utility with dedicated communication staff, we recognize Charlotte Water has more resources to do something like this than many water utilities in the U.S. But it doesn’t take a lot of extra resources to make the CCR more valuable for you and your customers. It just takes thinking through it a bit with your customer hat on.