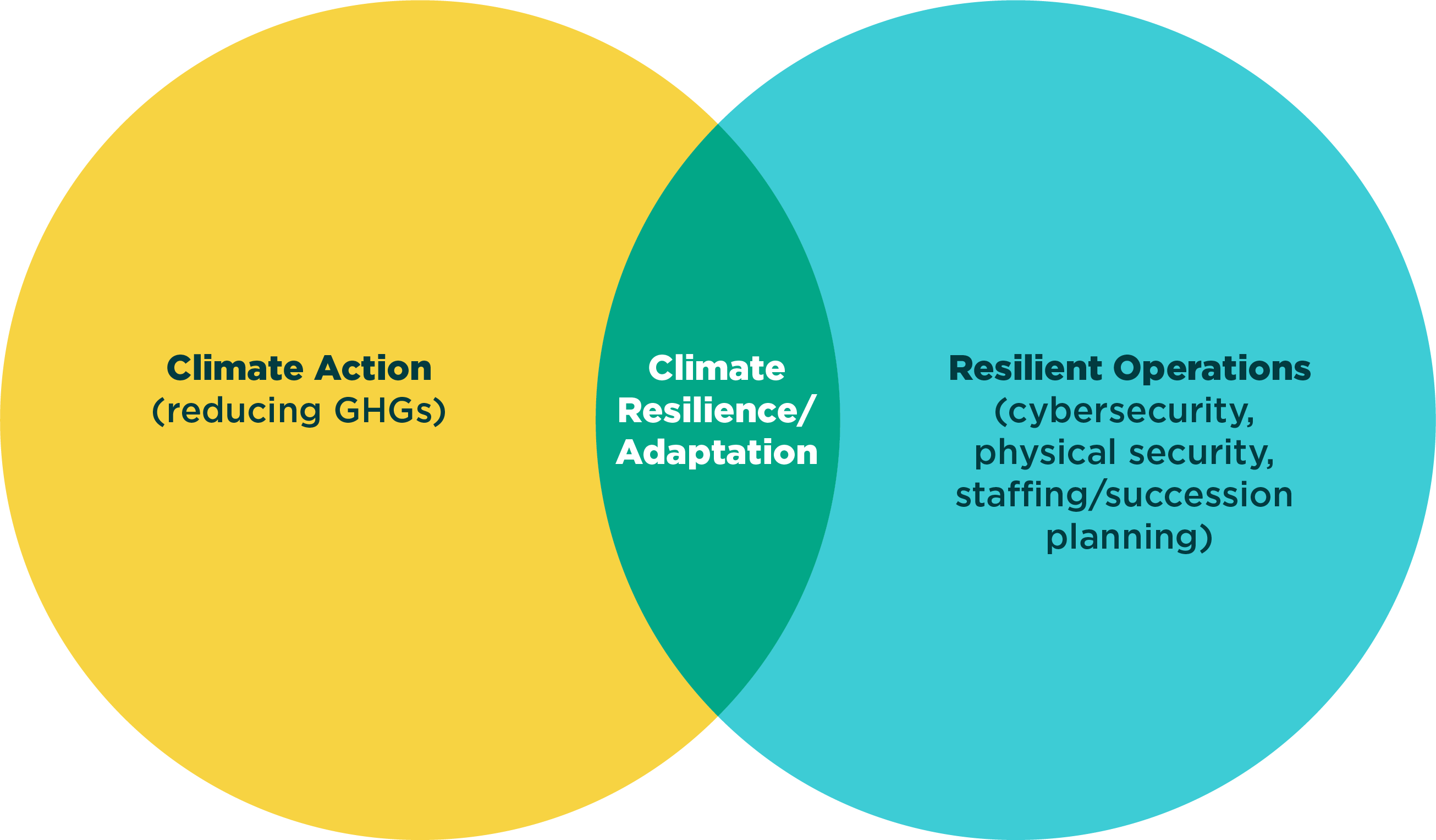

To be sure, climate adaptation within the utility space is the sweet spot in the Venn diagram of climate action planning and resilient utility operations. The figure below shows that climate action (on the left) can be thought of as both proactive measures to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and reactive measures to adapt to the new climate reality. On the other hand, resilient operations (on the right) comprise preparedness and recovery plans in reaction to both climate-related and other type of operational disturbances. As we talk about “resiliency,” it is best to raise the question, “Resilient to what?” rather than just assume that resilience must always be associated with climate change. In fact, the answer to that question from utility leaders at the forum referenced to the definition of resiliency laid out by the America’s Water Infrastructure Act (AWIA) of 2018. AWIA required water utilities to assess likely environmental, cybersecurity, and operational risks and to produce emergency response plans to enable recovery. In this instance, resilience is an operational concept subject to regulatory oversight. With increased focus on both cybersecurity and disaster recovery planning that is being signaled by the federal government, we may expect that oversight to increase over time.

Resiliency proficiency also means scaling the changes that the organization is willing and able to undertake to mitigate climate risks and recover from disruptions to its operations. The leadership of the utility may be pushed from one scale of change for the organization to the next by an extreme event in their service area. For example, major flooding following an unusually intense rainstorm could bring an increased focus on stormwater management in the community, which then heavily influences the capital improvement plan (CIP) for the municipality. Additional measures could include new methods of operations, increased staffing, and new financing mechanisms to enable implementation and sustain support in response to community demands for infrastructure that keeps their roads and homes safe from flooding. At the forum, this movement into a new scale of operations was well described by Dr. Casey Brown of University of Massachusetts Amherst through his characterization of utility operations as “persistent,” “adaptive”, or “transformative” compared to pre-disturbance mode. Thinking about “adaptive” or “transformative” operations can be daunting for some utility leaders struggling with staffing shortages and tight budgets. However, the increasingly unpredictable reality that they face may push them to think bigger in the near or medium term.

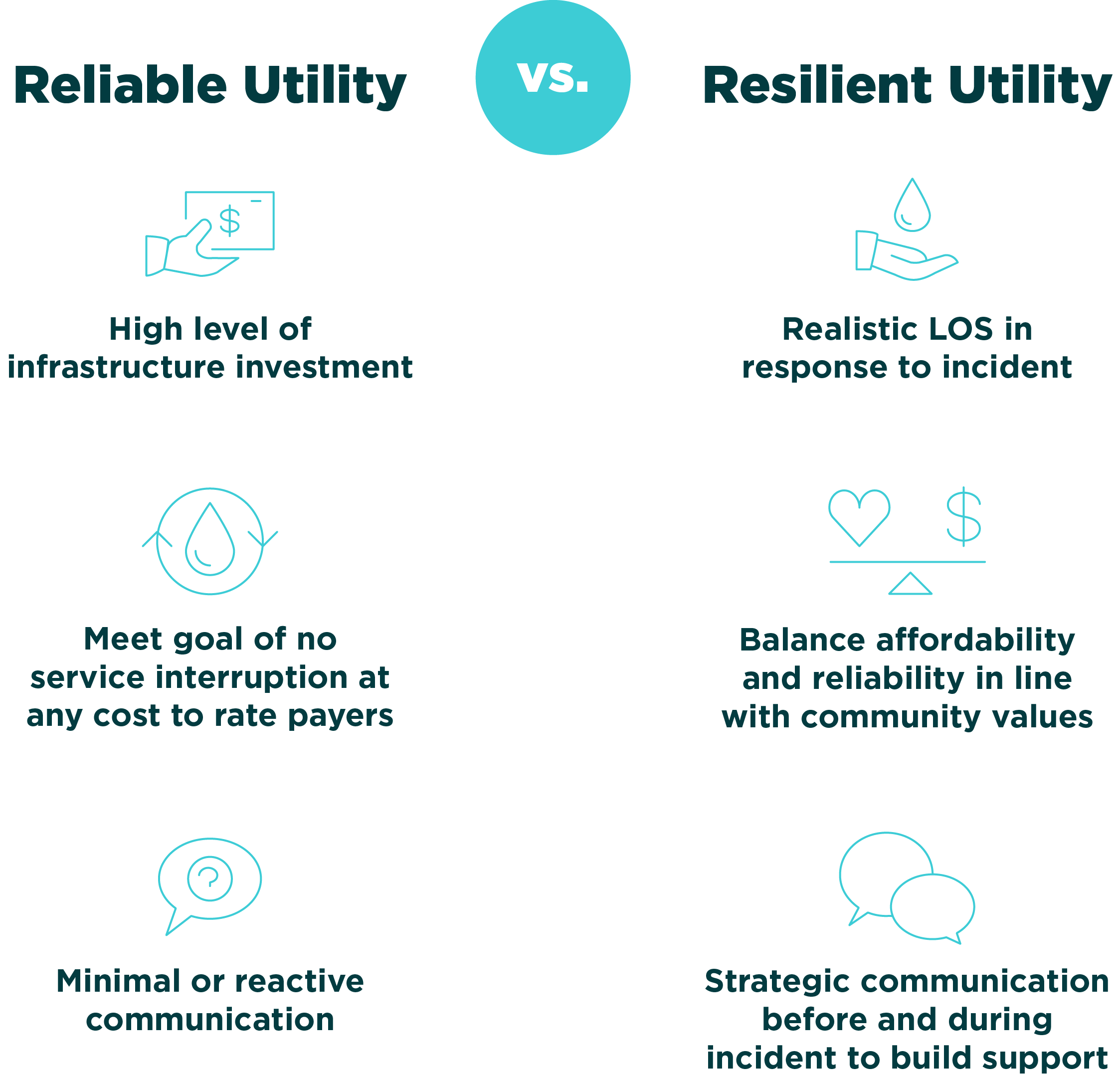

The scale of the operational response leads us to a third concept of resilience, which urged the attendees to ask the question: “Resilient to what degree?” The current assumption for most water, wastewater, and stormwater utilities is that they must operate without service interruption. This assumption of a reliable, continuous level of service is implicit in their mission to protect public health and safety. However, as the nation’s utilities begin to grapple with more unpredictable weather, is it reasonable for a community in the Southeast to expect no flooding at all during unprecedented rainstorms or hurricanes; or for a municipality in the West to plan for only minimal irrigation restrictions during multi-year droughts? The toughest question many utilities are asking is: “Are our customers willing to pay more for more certainty in terms of how we mitigate climate challenges and other risks, or would they prefer to have more risk and pay less?”

This important question gets at the heart of the matter: if resiliency is the ability to bounce back from a disturbance, then to be resilient, a utility must define the desired state of normal operations that it wants to return to within a reasonable time frame and at a reasonable cost. The definition of that “desired state” or the level of service in the immediate aftermath of a disturbance may be influenced by many factors, not the least of which is regulatory. Other factors that influence it, as well as the “reasonableness” of recovery times and associated costs, may include the:

The answers to these questions may be as variable as the weather, but the illustration above shows how we are shifting our thinking in terms of a 21st century resilient utility vs. a traditional reliable utility.