Over the last several years solid waste managers have dealt with a significant number of challenges including:

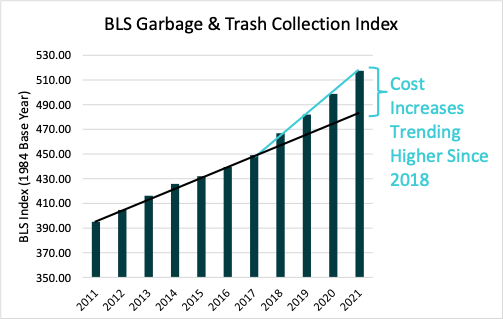

Evidence of these challenges can be seen in terms of rising costs for service. Until 2018, annual increases in solid waste fees were about 2% (per Bureau of Labor Statistics’ garbage and trash collection index), but now the average annual increase is 4%. These challenges and cost increases are placing additional pressure on solid waste managers who need to figure out how to fund their waste collection and disposal systems.

Raftelis recently surveyed solid waste managers about financial planning. Based on our experience and our survey responses, we identified five key areas to focus on to achieve a successful financial plan:

The solid waste mangers we work with said their ultimate goal is always to secure support for the resulting financial plan so they identify goals and objectives that align with their organization’s key stakeholders—public officials, staff, and ideally members of the public. A good place to start is with your organization’s strategic plan and mission, which can help ground the financial planning goals to support the broader objectives of the organization.

For example, if your local government is focused on specific initiatives such as waste diversion; reduced recycling contamination; or infrastructure replacement or expansion; the financial plan should have funding to advance these initiatives. This makes it easier to garner support because there is a clear link between what the stakeholders will get from the financial plan and how it aligns with their interests and objectives.

There are often goals and objectives that run counter to other objectives such as minimizing the need to raise user fees and fully funding the near-term cost of operations, (e.g., we don’t want to raise rates, but we agree we need more funding for equipment). That’s why focusing on goals and objectives first can help achieve the most return on your objectives for a financial plan. Finding this balance in the financial plan is what often drives the need to run what if analyses to determine what it takes to achieve one objective at the cost of another (e.g., minimizing user fee increase vs. maintaining or enhancing service levels in an environment of rising costs).

If you think what if scenarios will be a part of your planning, start with defining your baseline system requirements. A review of recent historical trends and the current fiscal position will help you assess if it’s where you want to be. Key components include trends in waste generation and service level requirements, operating capacity, operating expenses, contractual arrangements, and capital needs.

Sometimes the results of these exercises can present a positive financial picture but fail to capture life-cycle costs and long-term liabilities. Moreover, the maintenance cost of infrastructure and assets are not static and tend to increase with age. If you don’t account for these costs, you’ll miss an opportunity to communicate the total cost of service to stakeholders and risk being locked into a financial plan with limited flexibility that may result in deferring needed investment.

A simple strategy to avoid this pitfall is to first capture the future costs and then amortize the costs over the remaining period before the expenditure is expected. Once you have captured the lifecycle costs, a picture of current and future costs emerges as the baseline for the financial plan. At this point, you can confidently list and identify potential changes in operations to determine the financial implications from where we are going to where we want to be.

A financial plan risk is anything that could result in a material change ending in less financial resources or increased costs that limits the manager’s ability to fully fund operations. In the last few years, we have observed that planning risks can materialize in the form of a change in foreign policy, a pandemic, high inflation, increased severe weather events, ransomware attacks, and increased contractor fees. Developing a financial plan that mitigates these potential risks requires thinking through the probability of certain events and defining bookend assumptions to stress test the financial plan.

Stress testing exercises can help identify if a financial plan has adequate financial resources to cover unexpected events and highlight deficiencies, which may result in targeting greater cash reserve balances. The best and simplest method of mitigating risks to any financial plan is to maintain conservative assumptions in the development of the baseline requirements. Assuming slightly higher inflation or waste generation can build contingencies into your plan to help ensure success.

Anyone with a vested interest in the results of a financial plan can be defined as a stakeholder to the financial plan. For example, communication within the organization is key to identifying the necessary data and assumptions to develop the financial plan and provide feedback to staff about implications from budget requests. However, the trajectory of an organization is ultimately decided by the governing body of a municipality. It is important that elected officials and the public trust staff when being presented information. Presenting to an elected body that doesn’t trust staff or questions the integrity of the financial plan usually does not result in successful implementation. Trust can be developed by ensuring the information and data is accurate and well communicated through multiple channels including reports, presentations, and one-on-one meetings. More frequent communication provides necessary feedback to the solid waste manager about the elected officials concerns and allows the solid waste manager to directly address concerns and provide necessary context to garner support for the plan.

Working to identify key performance indicators (KPI) to measure desired operational and financial goals helps you assess whether your organization is on the right path. These measures should be tailored to your organization, operations, and needs. Operational KPIs may include items such as missed collections, safety records, tons collected and recycled, or other operational metrics that inform a manager of the solid waste system’s operating condition. While most solid waste managers are familiar with operational KPIs the more well-rounded manager is versed in financial KPIs.

Financial KPIs include metrics such as days of cash, debt service coverage, free cash flow for capital reinvestment, among others. These financial metrics sometimes track the amount of cash reserves in terms of expenditures such as the amount of days of operating expenses to help assign meaning to the amount of cash reserves an organization has. Incidentally these measures are more often tracked by financial managers who may not reside within the solid waste organization. In these situations, it is critical that solid waste and financial managers work together to develop an internal financial policy and financial KPIs that are meaningful to help mitigate risks. Working as a team to establish cash reserve targets that are tied to specific risks or needs such as a minimum operating reserves for working capital or storm reserve to help fund clean-up is a great place to start. Ultimately what we seek to measure with financial KPIs is the ability of the organization to handle planned and unplanned events. KPIs provide solid waste managers with an important feedback loop to adjust operations, or the financial plan as needed.